Part 1: Obtaining planning approval in Green Belt and AONB for a new Self-Build Passivhaus dwelling

Amanda Henderson of Hetreed Ross Architects shares her experience…

The Problem

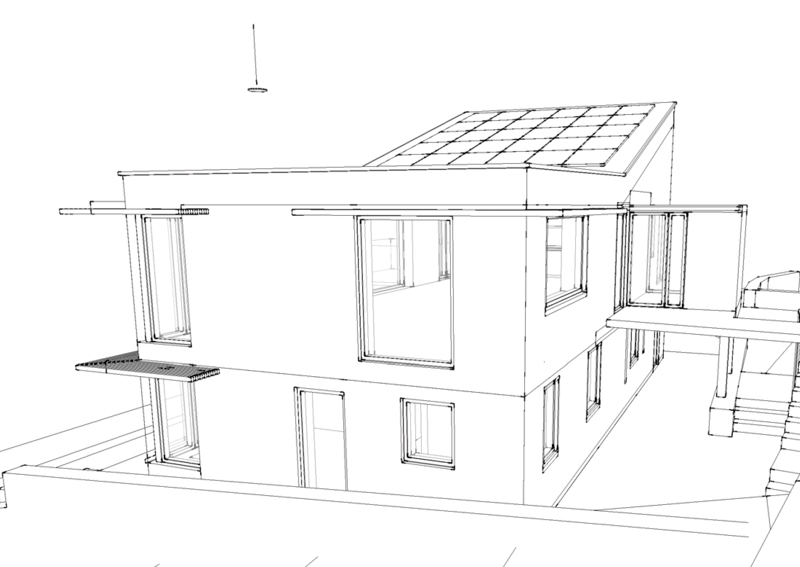

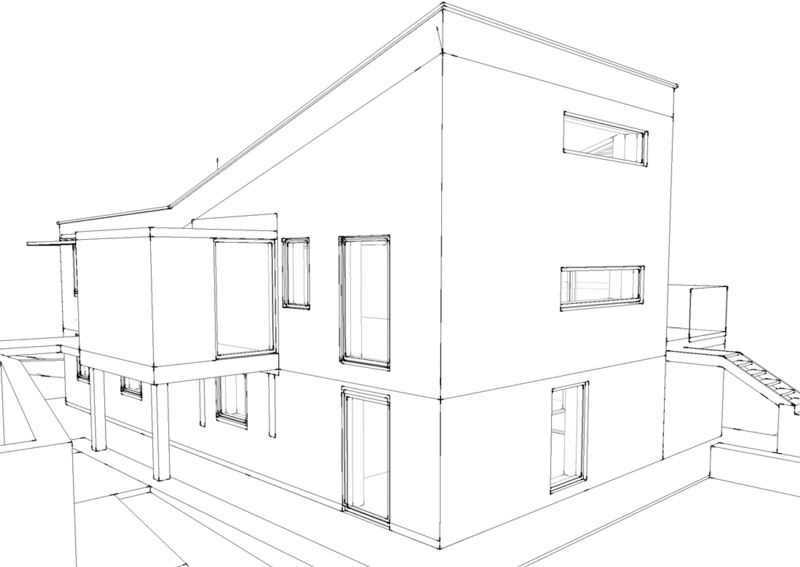

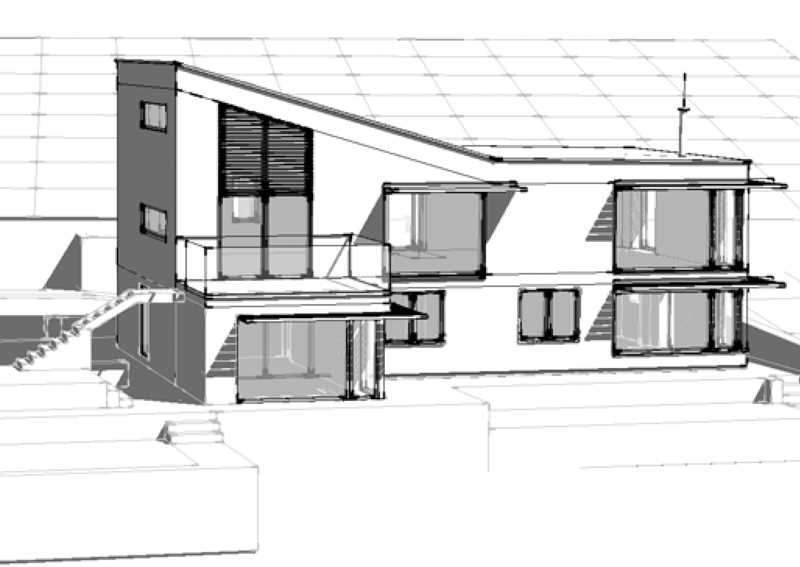

A self-build Passivhous project started with a big problem: a dark, damp, uninsulated and unstable house in a beautiful setting with stunning views. It is on a steep site with very limited vehicular access but plenty of land. The house does not function well as a family home, it is poorly planned, has low headroom, lots of changes in floor level – even in the middle of the kitchen! It is freezing in winter, overheats in the summer and garden access is indirect at best. But when you have watched the sunset from the terrace, the appeal of the site is clear.

The Route to Approval for a self-build Passivhaus in Green Belt

It is not an easy path. In this case the site had a house on it already, which provides one of the more straightforward routes to an approval. The next step is to justify demolition of the existing property. In this instance it was fairly easy, there was an old quarryman’s cottage probably a one-up one-down that over the centuries had been lost in ill-planned and poorly built additions. The result was a poorly functioning, ugly house that suffered from damp and structural movement. To put all the problems right was simply not worth it, either financially or practically. I can say that as it is my house! The planners had no difficulty in agreeing that demolition was appropriate and did not even demand a structural survey. If the house had been listed it would have been a different story.

Volume is key

In Green Belt any replacement house must not affect the “openness” of the countryside or be “materially Larger” than the original or pre 1948 dwelling. This is open to some interpretation and in practice means that volume and form of the proposals have to be very carefully designed. So after discussions with the planners it was broadly established that the volume of my proposal had to be under 50% larger and ideally around 30%. The approved scheme was somewhere between the two and a bit of research was required to ascertain when the various extensions had been constructed.

Precedent

A planner will tell you every scheme is decided on its own merits and that may well be the case. But if there are a few similar situations local to your property where approval has been granted for something that is perhaps “borderline” in planning terms, it is helpful to cite them as examples of precedent. We spent many hours poring over planning records and did establish there was a great deal of precedent for approving dwellings in the locality that were a lot larger than the pre 1948 dwellings they replaced or enlarged.

Time and Bat Surveys

It was not a quick process, partly because the work to design it had to happen in my spare time, of which there was very little. We made a pre app with a large scheme – too big but it did give us something to reduce, made a full application with a smaller scheme and then had to withdraw it and wait whilst bat surveys were carried out the following year. Fortunately no bats were evident so we could reapply and inevitably I took the intervening time to further develop the design, chipping away at the volume some more. If bats or other protected species are found in a property you are trying to demolish, don’t despair! But it may mean you have to design in some ‘mitigation’ either in the building or in the garden – and it can affect timing of the build…

Winning support with Contemporary Design

Frustratingly as an architect the most important factor in obtaining the approval on this site was getting the volume right. However, the planners were very supportive of the contemporary design and it undoubtedly made the process easier, especially with the local parish council. We did spend time showing the scheme to neighbours and the PC to keep them informed and to gain their support. That meant the submitted scheme did not receive many objections, the only one we did have was relating to concerns about disruption during construction, understandable as the property is sited along a single-track, dead-end lane. We plan to keep the spoils of demolition and excavation on site as much as possible, rubble can be useful for creating some flat areas on a steep slope, it will save money too.

Sustainability

While I was designing the house I was also learning about Passivhaus and came to the conclusion that it would be worthwhile designing my own home to follow the Passivhaus principles and if possible to get it certified. It is not ideal in terms of form and orientation (more of that later) but I like a challenge and, even if we fail, we will hopefully end up with a building that performs better than most.

Our planning approval came with a condition that the building is designed to achieve “a level of energy performance at or equivalent to Level 4 of the Code for Sustainable Homes”, I am not sure what that is going to mean to us as the Code is withdrawn and “equivalent … energy performance”? I will need to understand what is meant by that, the Code uses SAP as a calculation method which is nothing like as accurate/rigorous as the Passivhaus PHPP method for energy performance (in my humble opinion) so hopefully it will be a walk in the park…

Next steps for the self-build passivhaus project which I will share in upcoming blogs

- What materials shall I use?

- How will I build it?

- Investigating mortgages for self-builds.

- Who will I appoint to help me?

- Will I need to put in a new planning application or revise the one I have as the scheme develops?

- Challenges of designing to Passivhaus principles on this project. Building warranties?

- ….and much more besides…

Amanda is an Architect and Certified Passivhaus Designer